Education gaze traditionally foregrounds student agency and pedagogical approaches to smartphone distraction in the classroom try to reclaim an illusory independent human agency.

The general recommendation for dealing with smartphone distraction in the classroom is that teachers need to evolve their teaching style and have teaching strategies for teaching in contexts where the students are distracted on their smartphones with activities unrelated to schoolwork in class.

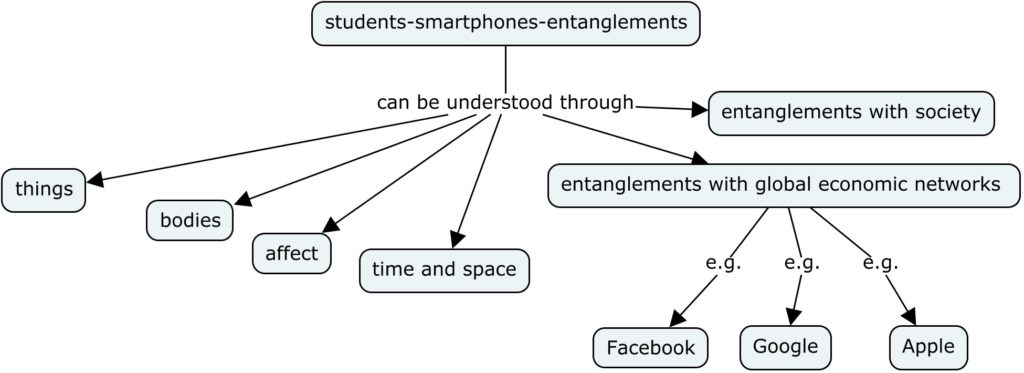

The argument is that students do not have independent agency, instead students’ lives are entangled with their non-human companions, their smartphones.

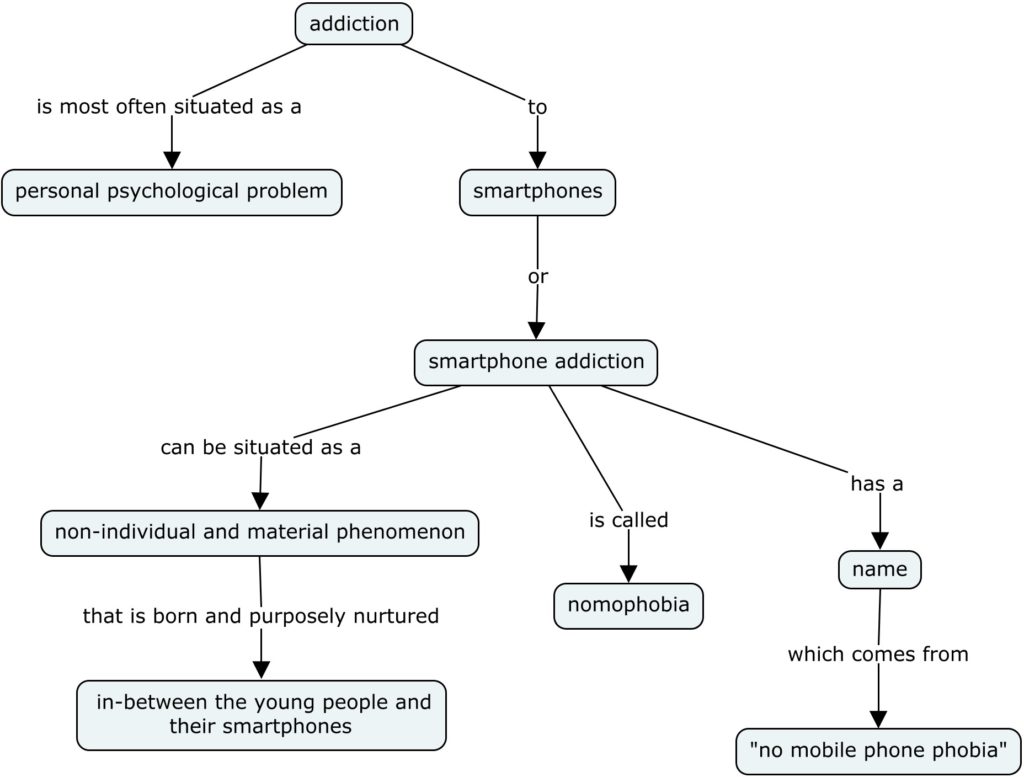

The affective nature of students’ engagements with smartphones is companionship. Smartphones become almost like body parts, which are obviously used as hands and eyes. Students refer to smartphones as “best friends” or “soul mates”.

We see this phenomenon among adults also; “smartphones have become more intimate to us than our best friends, even our lovers. While we’re quite happy to leave our televisions, desktops, laptops and even tablets behind on many activities, we’re less comfortable about ever being without our smartphones. And unlike other essential objects such as keys, wallets and purses, our relationship with our smartphone is about being connected, about presence management, about identity. In other words, more than a best friend, our devices are becoming extensions of ourselves.”

(David Vogt, ETEC 523 course, Summer 2020, UBC)

Affect is at the center of and connects student’s lives, digitality and education. It is through affect that engagements with smartphones acquire their life-changing intensity.

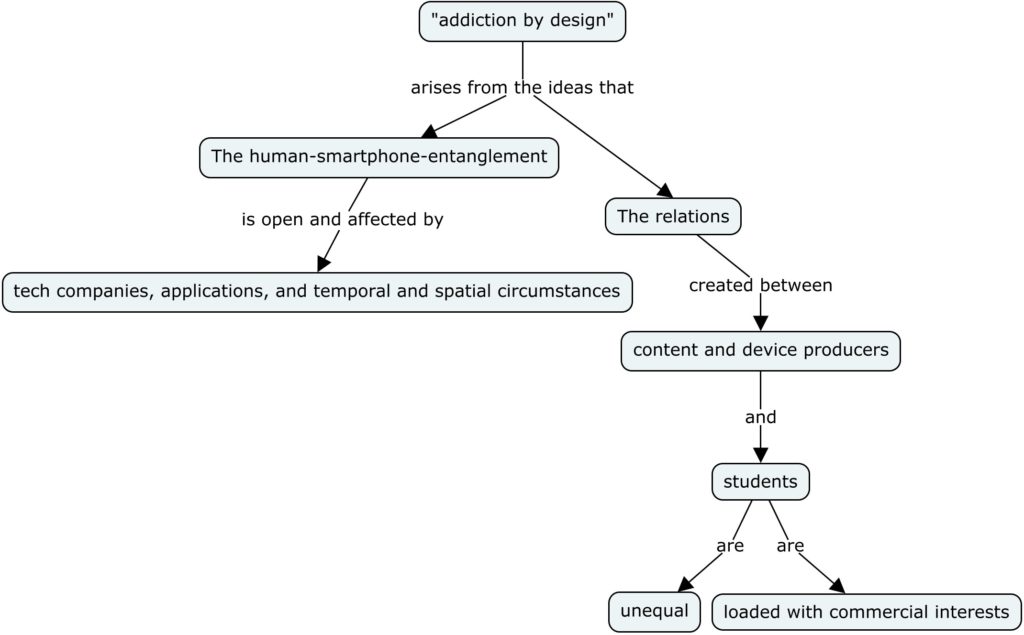

These affective intensities do not simply emerge from nowhere, but they are partly result of meticulous market research and corporate strategy, with the software and hardware companies aiming to maximize the time their users spend engaged in their products.

While students have access to their smartphones, the smartphones also have access to the students. As such, events, ideas and provocations outside the realm of education flow into the classroom via the students’ smartphones.

The relations between students and their constant digital companions, their smartphones, cannot be reduced to instrumental pedagogical relations.

The digital companionship, attachment and entanglements between young students and their smartphones should be considered at an ontological level, not merely at a pedagogical level.

Therefore, more stimulating and engaging pedagogy alone is not the answer to smartphone distraction when students already have their smartphones in their hands.

My answer is stimulating and engaging pedagogy plus nudges; when students already have their smartphones in their hands we need to use adaptive digital nudges at appropriate times to nudge the student to get back on task.